the long dissociation

why so many of us learned to survive by staying slightly absent

absence is what happens when something meaningful doesn't arrive for so long that we stop expecting it.

we adapt without realizing we’re adapting. we want less. we expect less. we train ourselves not to reach.

the calculus is invisible but precise: desire becomes embarrassing. we idolize nonchalance. earnestness feels unsafe. caring too much starts to feel like a liability.

we learn to moderate our investment in proportion to our disappointment. we learn to stay light, to keep moving, to not let things land too heavily.

somewhere along the way, many of us learned to keep going by staying just a little bit gone. we learned to live at a slight remove from our own lives, present enough to function and absent enough to endure.

naming it

it’s not apathy.. it’s not burnout.. it’s not even nihilism.

the long dissociation is a sustained, low-grade separation from our own life force. not checking out completely, but just enough to function. this didn’t happen overnight, it accumulated slowly, quietly, adaptively, like sediment settling at the bottom of a river.

the long dissociation is what happens when overwhelm lasts longer than our capacity to metabolize it.

raquel s benedict accurately described the problem in a viral 2021 essay called “Everyone Is Beautiful and No One Is Horny”. “No one is ugly. No one is really fat. Everyone is beautiful,” she writes. “And yet, no one is horny. Even when they have sex, no one is horny. No one is attracted to anyone else. No one is hungry for anyone else.”

how we got here

dissociation is intelligence. our nervous systems are remarkable instruments of adaptation. when the conditions demanded it, they responded with precision.

think about the conditions: constant crisis bleeding into the next crisis, endless information streaming through our devices, too much suffering without any container strong enough to hold it.

the nervous system, faced with input it cannot process, makes a rational choice: feeling everything wasn’t possible so the system learned to feel less. this is survival intelligence at work.

the distance gave us something valuable: functionality, productivity, social acceptability.

it allowed us to show up, to perform our roles, to meet our obligations. It gave us distance instead of devastation. numbness instead of collapse.

the long dissociation didn’t mean we stopped caring. it meant caring became unsustainable, so we learned to care less acutely, less completely, less dangerously.

This space is better when more people speak up. You’re welcome to join the conversation, however big or small your thoughts feel.

what it costs us

vitality. imagination. initiative. desire. not all at once, not dramatically, but gradually. the way color fades from fabric left in sunlight too long.

life becomes something lived competently but thinly. engagement without intimacy, opinions without investment, movement without momentum. we go through the motions with skill, but something is missing. we’re there. but we’re not really there.

how can you build something when you are watching from a distance? distance dulls responsibility. absence weakens authorship. the choices we make feel less consequential when we’re only half-present for them.

the life you want requires your participation.

the nonchalance epidemic

detachment has become socially rewarded as coolness and untouchability. distance is perceived as sophistication. if nothing matters, nothing can break you.

commitment becomes dangerous. belief feels naive. meaning requires vulnerability.

nonchalance promised safety, but it asked us to stay absent from our own lives. to remain removed from the very things that give our days weight and texture.

what won’t help

the way forward is not through forced sincerity or performative vulnerability. emotional exposure is not virtuous.

intensity without integration, feeling without groundedness, none of these help.

what helps is restoration of presence.

https://youtube.com/shorts/eJG5x0wDXPc?feature=share

meaning as practice

meaning is a practice. one that happens in increments.

aliveness comes back in doses.

in practice, it looks like taking one thing seriously again. choosing to care without certainty. staying with discomfort.

meaning grows where we keep showing up, even when we’re not sure why.

I write for free, once or twice a week, but the real joy is hearing from readers. You’re always welcome to respond. Hit ‘reply’ or send me a message below.

coming back

we can’t simply rip dissociation away.

it must be loosened gently, with curiosity and attention instead of urgency.

the long dissociation protected you for a reason. it kept you safe when falling apart wasn’t an option.

gently untying the blindfold might look like pausing before you answer, “how are you?”

it might look like noticing when you are performing engagement rather than feeling it.

we don’t heal the long dissociation by demanding more of ourselves.

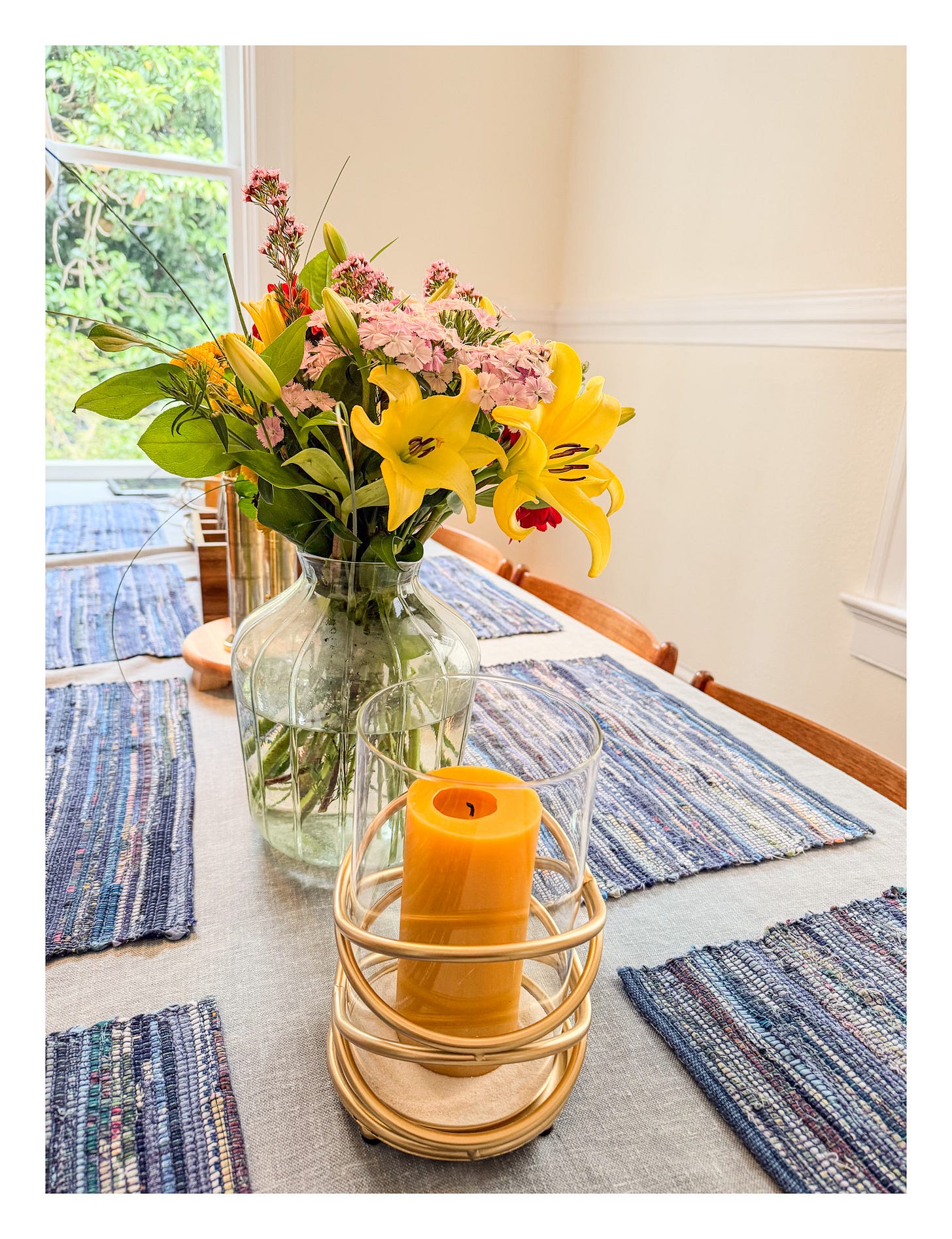

consider a bouquet of flowers. they don’t fix anything. they don’t solve problems or reverse damage. they don’t last. maybe they will be around for a week if you’re lucky. they serve no utilitarian purpose.

but, the gesture matters. the act of choosing them, arranging them, placing them where you’ll see them.

the participation matters.

it is a small act of presence.

a refusal to stay entirely removed.

the long dissociation taught us how to survive. it was intelligent, adaptive, necessary.

but survival was never the same thing as being alive.

and perhaps now, slowly, carefully, we can begin to tell the difference.

FYI: I’ve started a weekly newsletter called For People and Planet. It’s a place where I highlight what’s working in the fight for a more balanced future. You can read it here: forpeopleandpla.net

Further reading:

For more like this, follow me wherever you connect with friends:

Bluesky 💖 LinkedIn 💖 Mastodon 💖 X 💖 Instagram 💖 TikTok 💖 Threads 💖 YouTube 💖 Facebook

With love, Bri Chapman

As someone who has in the past been often accused of being too expressive about my caring or even caring too much ("this is just business, not personal") I have sometimes envied those who are able to remain more detached, more compartmentalized: there is a real value in the detachment I have seen practiced, as it allows the practitioners (as you point out) to endure and survive difficult situations they might otherwise have not made it through: Caring, and acting upon that caring can and does in many cases result in forward movement, positive change, building something new, fixing something broken, etc. But that same caring and acting on it can also result in defeats, loss, rejection, and exile.

This brings to mind the famous question of Hamlet:

Whether 'tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,

Or to take arms against a sea of troubles,

And by opposing end them: to die, to sleep

No more; and by a sleep, to say we end

The heart-ache, and the thousand natural shocks

That Flesh is heir to?